By Meryl Robinson

In 1998, I longed for a one-piece snowsuit. My cousin had one, and to me, it was the epitome of alpine style.

Outerwear fashions have traveled a long, chilly road from the sublime to the ridiculous. But these days, technology has given us fabrics that make it possible to play all day in the snow without suffering.

In 1998, I longed for a one-piece snowsuit. My cousin had one, and to me, it was the epitome of alpine style. It was black, decorated with ‘90s-styled flowers in all shades of neon (actually, it was rather subdued for the ‘90s). It was a point in ski fashion that I’m sure many skiers relate to, whether you like to admit it or not.

Ski wear and ski wear technology actually had a lot of work to do before getting to the glorious, blinding ski wear of the ‘90s (and then the blinding ski wear of today). It first had to pass through the eras of scratchy wool sweaters and stretch pants.

In the very early days skiers who wanted to stay warm counted on wool. Sweaters, pants, jackets, hats—you name it, skiers wore it in wool. Happily, the invention of nylon and its quick adaptation into ski fashion in the 1950s gave skiers more options. Synthetics were soon essential: wool-nylon blends were used in the stretch pants that made a name for Maria Bogner while Klaus Obermeyer earned fame with nylon windshirts. These windshirts, by the way, were worn under a wool sweater for a day on the slopes.

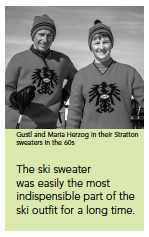

The ski sweater was easily the most indispensible part of the ski outfit for a long time. Paired with a cotton turtleneck (horror of horrors), the wool ski sweater would be an enduring part of the “ski uniform” through the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s. Even now, the ski sweater is a necessity, although recent generations might be made of recycled soda bottles or a few different kinds of wool.

As glimpsed in the archival pages of this magazine, Southern Vermont ski mountains were something of a microcosm of ski chic from the 1960s on. Ski wear fashion shows put forward outlandish styles that hardly looked chairlift-worthy while style forward ski shops supplied skiers with pants, turtlenecks, and ski sweaters from brands like Beconta and Roffe.

As glimpsed in the archival pages of this magazine, Southern Vermont ski mountains were something of a microcosm of ski chic from the 1960s on. Ski wear fashion shows put forward outlandish styles that hardly looked chairlift-worthy while style forward ski shops supplied skiers with pants, turtlenecks, and ski sweaters from brands like Beconta and Roffe.

Persistent as the ski sweater is, other parts of the ski uniform changed around it. The 1970s traded the wool- nylon stretch pant for more insulated gear, some looking long and lean, some with a decided bell-like flair. These were the early days of C.B. Vaughn’s SuperPant, an insulated pant with zippers up the side. C.B.’s pants were some of the first in a growing trend toward ski wear designed for performance.

It was in the late ‘70s that an innovation heaven-sent finally appeared: Gore-Tex. A stretched-out form of a mouthful of a polymer (you also know it as Teflon), the Gore-Tex membrane could be bonded to an outerwear fabric to make it waterproof and windproof, yet breathable. In other words, it was magic.

Nevertheless, “the choices then were limited,” recalls Sue Rice, co-owner of Equipe Sport and a former ski wear buyer for Stratton Mountain. “The CB Apollo jacket was big in the New England scene. It was a down parka with a fitted waistband, but there was nothing technical about it in terms of fabric.”

It was in the late ‘70s that an innovation heaven-sent finally appeared: Gore-Tex. A stretched-out form of a mouthful of a polymer (you also know it as Teflon), the Gore-Tex membrane could be bonded to an outerwear fabric to make it waterproof and windproof, yet breathable. In other words, it was magic. CB Sports (based in Manchester) distinguished itself as the first ski wear company to use Gore-Tex in its outerwear, but it would take some time for the technology to become widely used.

At the turn of the decade, skiers had pants primed for performance and the first jackets that could stop whatever Mother Nature dishes out.

Where to next?

Stretch pants, shoulder pads and neon.

“Stratton in the ‘80s was pretty glamorous.“

–Sue Rice, Equipe Sports

Ski outfits in the 1980s borrowed more than a few pages from main-stream fashion’s book. The slim fashions of the past decade gave way to bulky jackets with broad shoulders, paired with tight, high-waisted pants. Stretch pants regained a share of the pants market when not edged out by one-piece ski suits.

According to Sue Rice, “one of the funniest styles was this handpainted one-piece suit from Bogner. Each suit was done by a different artist, and they all came out very different.” The suits were white with outrageous paintings—one had bright, broad brushstrokes; another, the Mona Lisa. “We showed them in picture frames because they were actually beautiful. We sold them all,” she says. “Stratton in the ‘80s was pretty glamorous.”

More than ever before, apparel makers turned their attention to what skiers wore under their brightly colored gear. In the face of the modern miracle synthetic fabrics, cotton was the next for the chopping block. Until then, layering dogma called for a cotton base layer, a wool sweater for insulation and insulated parkas to fend off the elements. But, of course, cotton makes a miserable base layer and now, we wouldn’t wear it if you paid us handsomely. Hindsight is 20-20.

While some were distracted by Michael Jackson and the first Macintosh computers, the titans of ski wear were busy reinventing synthetic base layers. Patagonia was first with polypropylene and then polyester—that resisted water to wick sweat away from the skin, keeping the wearer drier and warmer. It was also the first company to use polar fleece, a lofted synthetic fabric that provided something as yet hard to find: warmth without weight.

Polartec invented synthetic polar fleece in 1981, and Patagonia (then focused on the mountaineering community) began to use it in their products in 1985. Warm, light, and water resistant, polar fleece was a game changer. Now, it’s hard to consider skiing without it in one form or another.

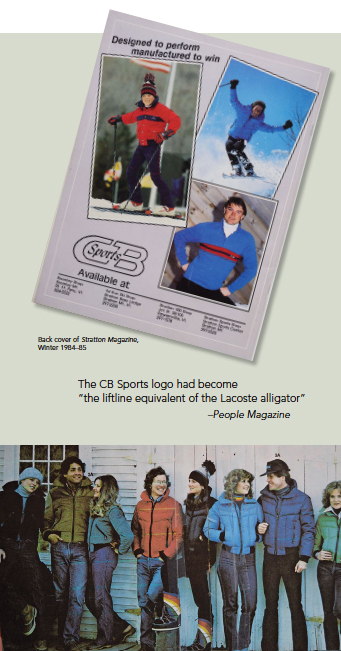

Meanwhile, the CB Sports logo had become “the liftline equivalent of the Lacoste alligator” (said People magazine in 1982). For skiers, at least. The ‘80s brought the first snowboarders to Stratton’s slopes, and the lines were drawn—both in the snow and in style. Seeking anything that didn’t scream “skier,” the new fashion faction first grabbed garish, logo-blazoned gear, then impractical jeans-and-flannel-shirt combos or androgynous, baggy outfits in all the lovely shades of dirt. When Olympian Betsy Shaw chronicled snowboard fashion in 2000 for Stratton Magazine, it had mostly gotten out of its awkward teenage phase. Functional and even enviable gear designed for snowboarders had begun to appear in the ‘90s, notes Betsy. From that point on, the ski and snowboard worlds would be locked in a tug-of-war.

Neon hues, mind-bending patterns and (what else) stretch pants took over the apparel ads in the ‘90s, when gear guides were suddenly populated by skis with curves. Shaped skis were a revolution partly pushed by parabolic snowboard designs, and they weren’t the only things borrowed and adapted. If you were anywhere near a mountain in the naughts, you understand Betsy’s quip: “there’s a plumber in every pipe.” It still rings true 15 years later, though the offenders are just as likely to be riding two planks as one.

While the gear under our feet was changing and apparel was attempting camouflage with a supernova, synthetic fabrics were sinking in on every level. Polyester and Gore-Tex (if you were lucky) took the outside; Turtle Fur neckies and Patagonia Synchillas were stuck in the middle; polypropylene got the place of honor next to skin. “Fashion was trumped by technical fabrics in the mid ‘90s,” says Sue. “Brands were defined by the way the product was built or spun to keep the moisture away.”

Of course, synthetics have their drawbacks as well (many, in fact). Polypropylene’s water-resistance makes it hang on to bad smells, as anyone’s long johns can attest after a season. Regular old polyester fabric and insulation is about as breathable as a plastic bag. The door was open for something better to come along, and it did—wool.

This was not the wool of scratchy sweaters and heavy pea coats. It was Merino wool, from a breed of sheep known for fine, soft wool and adaptability to different temperatures. Aside from naturally wicking moisture, Merino fibers are so fine that bacteria can’t grow on them, kiboshing the base layer odor problem. Its renewed edge was due to the ability to add some new technology—waterproofing laminates, wind-blocking outer layers—to what was already a wonder fabric.

Look through the tags on your most trusted gear, and you’ll see that polyester, polypropylene and merino are likely the basic materials, depending which layer you’re on. The building blocks may stay the same, but new weaving techniques and various treatments have helped fabrics become evermore waterproof, breathable and comfortable from the ‘90s to now.

And it’s not just skiers and snowboarders that can’t keep their hands off the new lighter, warmer and more technical fabrics. Now, “the outerwear brands are designing so much of what fashion is. They’re being copied in high fashion products, which is always kind of interesting,” says Sue. “I think the next thing will probably be more of the same, but better.”

All of which means we have fewer excuses to sit out that less-than-bluebird day. ◊

Meryl Robinson is a marketer and writer who lives in Brattleboro.