The Monastery Above Manchester Village

By Anita Rafael

The brittle, yellowed pages of old guidebooks to the Manchester area will tell you that there is a small hotel called the Sky Line Inn on the peak of Mount Equinox, but you will find no mention of a monastery. Today, on the same footprint where the hotel once stood, there is a modern visitors center, built in 2012, and inside, there is a great deal of information about the monastery located low on the west slope, and about the religious order that owns the entire mountain.

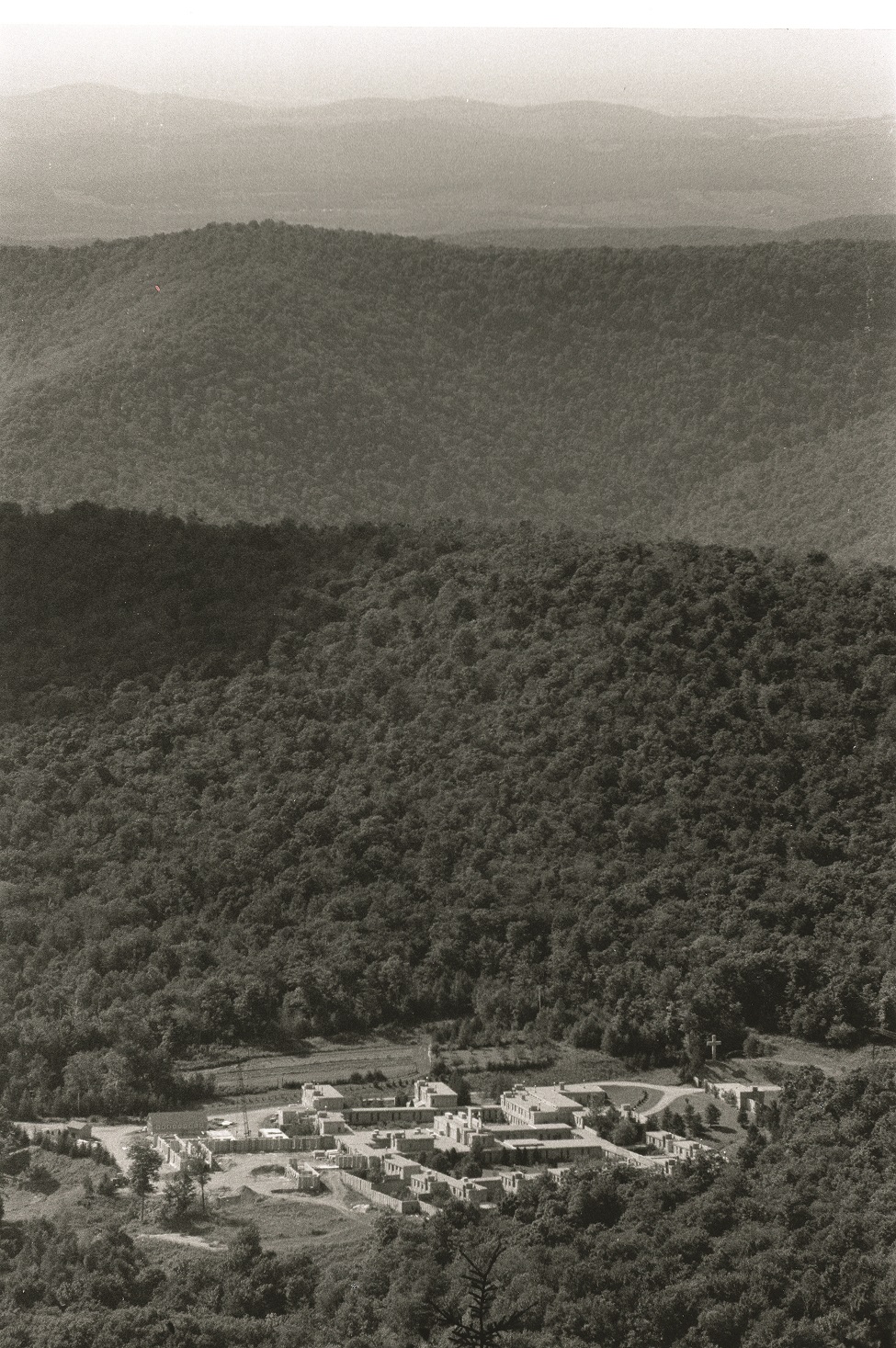

In a deep side valley, well below the summit of Mount Equinox, and located between two man-made basins (Hopper Pond and Lake Madeleine), there is a monastery where a small group of Carthusian monks live in silence, in prayer, and in solitude, but not entirely without an awareness of the way in which the world turns. From Memorial Day weekend through October, when the five-mile Skyline Drive is open (it is a toll road from VT-Route 7A south of Manchester Village to the top of the mountain), visitors may park their cars at a turnout at a midpoint on the climb called “the saddle.” From there, they have a bird’s-eye view of the monastery, far down in the distance. That scenic overlook is as close as the public ever gets to the monastery.

The singular mission of the 15 Brothers and Fathers who live at the monastery on Mount Equinox, from the time they find their vocation until the day they die, is to pray for the entire world. The monastery, officially called the Charterhouse of the Transfiguration, is one of 25 Carthusian sites around the world, and it is the only one in the United States. It opened in 1970. There are two others in the Western Hemisphere, in Argentina and Brazil. Most are as remote, or more so, than the Mount Equinox location, to abide by the Order’s call for seclusion. Although there is no monastery for Carthusian nuns in America, there are five in Europe, plus one in South Korea. The order was founded by Saint Bruno in the 11th century AD in France.

During a season where the amount of time and effort spent on planning holiday parties and gift shopping sometimes supersedes the few moments we may take for reflection, thinking about the way in which these holy men live and worship alone up on the mountain, the highest in the Taconic range, offers us solemn inspiration. Little is ever written about the monks, and few people know their names—even less is told about the paths these individuals have taken to be able to fully adopt the lifestyle of considerable sacrifice that their order compels.

“These priests have made a deep commitment,” explains Jeremiah Tarr, a member of the monastery’s Equinox Foundation board of directors. A retired Rutland businessman, he is one of five people who manage the business affairs for the monks. The monastery is funded by the earnings from the Skyline Drive and Toll House gift shop, by the logging on their 7,000 acres of land, by the leases for the various communications towers at the summit, by the sale of hydroelectric power generated by the waterways on the mountain, and by donations.

“Serving the monastery is one of the most rewarding things I have been part of in my life,” he says, “but I could not live like they do. A cloistered existence such as this is difficult, and yet, I have seen that, even in silence, these men express such profound inner peace and are happy.”

The monks who live at the monastery are either Brothers or Fathers. For four or five hours during the day, the Brothers undertake the manual labor that keeps the monastery functioning, such as cooking and baking, for example, while the Fathers dedicate themselves entirely to contemplative prayer. Each “day” actually begins at 11:30 p.m. for the monks because they believe that “nocturnal praise” is all the more ardent.

Together in church, the monks sing the Carthusian Chant, which is a form of Gregorian chant. Throughout the day and night, that is, every single day and every single night, at the toll of the tower bell, the Canonical Hours—Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, and Vespers—and multiple Masses are repeated in Latin. In the interims, the monks study, meditate, and pray alone in their cells. A man who is accepted into a Carthusian monastery, say, at age 35, and who lives there until his late 80s, spends a half-century solely dedicated to this practice with the intention of illuminating both his mind and his heart.

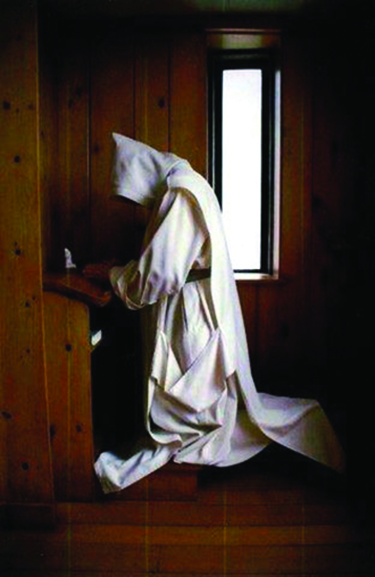

Each monk wears a white, hooded robe; the Fathers also wear a rough, woven penitential garment underneath called a hair shirt; and each lives alone in their own cell, spending most of the day and night there. Each cell has an oratory to kneel in prayer, a desk, a chair, and a bed with a thin straw mat. Each monk eats his single daily meal alone, delivered to him in covered metal containers through a small compartment with a hatch, except for one communal meal a week. Those in the Carthusian order eat vegetables, fruit, eggs, and fish, but no meat.

The monastery is a large complex and austere throughout—the cells, the cloister, the church, the chapter room, the refectory, the Brothers’ chapel, and the kitchen are built of 18-inch-thick, Vermont-quarried, unpolished, gray granite and bare concrete. The long passageways remain unheated, even though the annual snowfall on the mountain averages more than eight feet. Each monk warms his own cell with his own potbelly stove, storing cordwood on the lower level. “It’s been logged off the mountain by a contractor,” explains Tarr, “and long lengths are stacked in the monks’ individual woodbins through an exterior opening.” Each monk keeps a sawbuck and tools by the woodpile— saw, wedges, axe, and hatchet—to cut and split the firewood to fit into his stove, which gives him some physical activity during his protracted hours of silent study. In summer, he may tend a small garden plot outside his cell, planting what he will: flowers, herbs, or vegetables.

Tarr says, “Once a week, the monks take a long walk together outside. They walk during the winter, too, and then they wear snowshoes. During their walks, they can have conversations with each other.” The monks have no televisions, no radios, no telephones, and no internet. Their families may visit them, but only for one or two days, typically once each year. There is a building at the perimeter of the grounds where the monks may reunite with relatives, and since the day that the monks took up residence no women have ever passed through the gates. In the cemetery at the monastery, the graves have plain, unmarked crosses.

At a time when there seems to be a perpetual and mounting need for churches, missions, and ministries working to soothe social angst and ease human suffering, it seems anomalous that Rome would approve of any Catholic order that withdraws unto itself. Vatican Council II, opened in 1962 by Pope John XXIII and closed under Pope Paul VI three years later, acknowledged that, even in the modern world, it is the unconditional duty of contemplatives “to devote themselves exclusively to God in solitude and silence…no matter how pressing the needs for active apostolate might be.” [Perfectae Caritatis,7 ] The Church validates the Carthusians’ belief that their way of life provides “the most apt mean” through which a union between the human and the divine can occur.

It is inexplicably reassuring to know that at almost any time of day or night, in the worst blizzards of this winter and every winter, high on this darkly forested mountainside, there are monks with enduring faith praying for all mankind. The next time you look up at Manchester’s ridgeline, pause your gaze on the highest peak, and, at the very least, whisper amen.

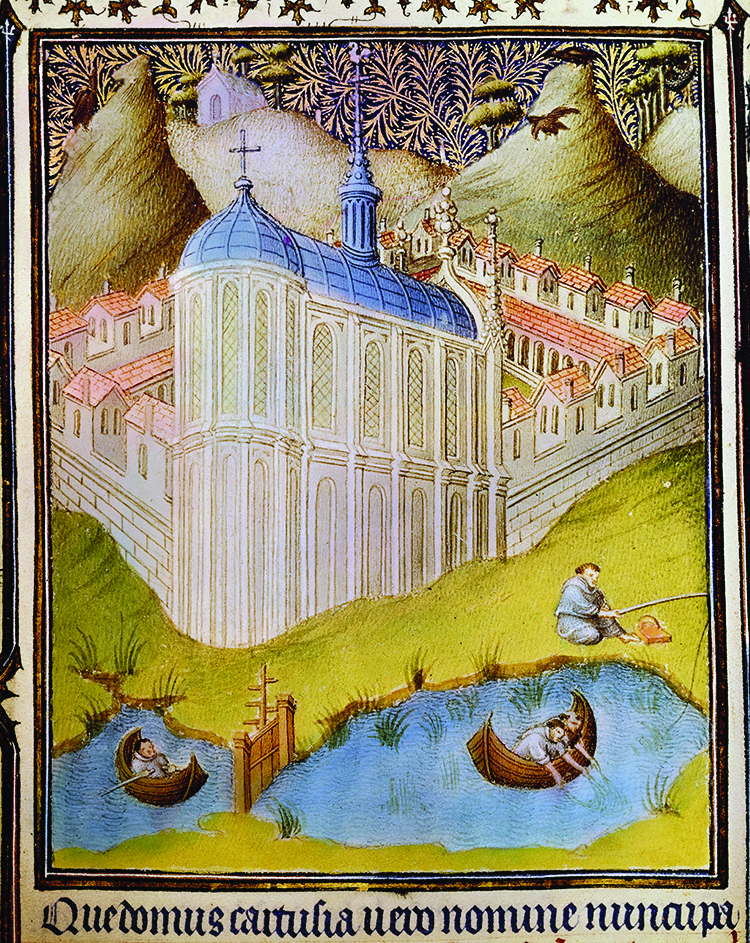

The Order

The name “Carthusian“ was taken from the Chartreuse Mountains in southeastern France. In a valley in this range, Saint Bruno and his six companions built his first hermitage in 1084. As early as the 1700s, the monks were distilling the green liqueur called Chartreuse, although at the time, it was intended as a medicinal elixir. To this day, the exact recipe—a combination of 130 herbs, plants, and flowers is only known at any given time to the two monks in France who, working in great secrecy, prepare the botanical mixture for the distillery. Open for tours, the distillery and cellars are located 18 miles north of Grenoble in the town of Voiron.

Details

The access road to the monastery is monitored, gated, and private. The public may not enter. To view a photo gallery of the site and the spaces inside the monastery, visit transfiguration. chartreux.org and choose the tabs for The Landscape, Inside the Monastery, and Inside the Cells.

To ask for prayers or Masses for any person, living or deceased, you may write to the monastery and send the name of the person or people who they are for, along with a note describing intention of the appeal. Normally, there is no acknowledgment. The monastery accepts offerings by check of a stipend of $10 per Mass (or whatever the donor can afford). The mailing address is Charterhouse of the Transfiguration, Carthusian Monastery, 1084 Ave Maria Way, Arlington, VT 05250

For details on the Skyline Drive, open Memorial Day through October, visit www.equinoxmountain.com.